Writing Crank from Scratch

A step-by-step guide to building Crank.js from the ground up, demonstrating how virtual DOM libraries work and showcasing advanced techniques with iterators and promises.

One of my goals when authoring Crank.js was to create a framework which was so simple that any intermediate JavaScript developer could conceivably write it from scratch. What I think makes this uniquely achievable for Crank is that its component model is built on top of JavaScript’s two main control flow abstractions, iterators and promises, allowing developers to write components exclusively with sync and async functions and generator functions.

The following is an attempt to prove that I’ve met this goal by rewriting the bulk of Crank’s core logic as a series of additive commits, with explanations for what I’m doing at each step.

Even if you don’t plan on using Crank, this essay may yet prove informative in that it will demonstrate the basics of how virtual DOM libraries work, and show you some advanced techniques for working with iterators and promises. I will also attempt to justify some of the design decisions I made along the way, as I make them. Moreover, the end result won’t just be a toy library, but something which looks very similar to Crank’s actual source code, making the jump from reading this essay to contributing to the project much easier, should you be so inclined.

At each step, we’ll edit a single file which serves as the Crank module, and present a unified diff of the changes. We’ll also provide a link to the relevant commit and snapshot for each step in this companion repository.

You can try out the module we create by referencing it from the following HTML file.

<!DOCTYPE HTML><html><head><meta charset="utf-8"/><title>Crank from Scratch</title><script src="https://unpkg.com/@babel/standalone/babel.min.js"></script><script>Babel.registerPreset("crank", {presets: [[Babel.availablePresets.react, {runtime: "classic",pragma: "createElement",pragmaFrag: "''",}],],});</script></head><body><div id="app"></div><script type="text/babel" data-type="module" data-presets="crank">import {createElement, Renderer} from "./crank.js";const renderer = new Renderer();const app = document.getElementById("app");renderer.render(<div>Hello <span style="color: red;">world</span></div>,app,);</script></body></html>

This file uses the Babel standalone transpiler to transpile JSX on the fly. We don’t transpile modern ECMAScript features, so you will need to open the file from an up-to-date browser. Alternatively, if you don’t want to use JSX, you can use the HTM template tag, which requires no transpilation. The examples in this essay will use JSX, but you are free to use HTM or any other alternative.

<!DOCTYPE HTML><html><head><meta charset="utf-8"/><title>Crank from Scratch</title></head><body><div id="app"></div><script type="module">import htm from "https://unpkg.com/htm?module";import {createElement, Renderer} from "./crank.js";const html = htm.bind(createElement);const renderer = new Renderer();const app = document.getElementById("app");renderer.render(html`<div>Hello <span style="color: red;">world</span></div>`,app,);</script></body></html>

This essay assumes an intermediate level of JavaScript experience, as well as some experience with a virtual DOM framework like React.

Step 1: Creating DOM Nodes #

The first thing we’ll need to do is to implement a createElement() function, so that the module works with JSX. While the React team is working on an alterative JSX output, we’ll stick to its original transpilation, where JSX element expressions are transpiled to createElement() calls, with the tag, props and children of the syntax transpiled to the first, second, and remaining arguments of the createElement() call respectively.

const el = (<div id="greeting">Hello <span style="color: red;">World</span></div>);// transpiles to:const el = createElement("div",{id: "greeting"},"Hello ", createElement("span",{style: "color: red;"},"World",),);

The other thing we’ll need is a renderer, a JavaScript class which reads element trees and does the actual work of creating and mutating DOM nodes. Importantly, the renderer has a render() method, which allows us to write code like the following to render a JSX expression into a DOM node.

renderer.render(<div>Hello <span style="color: red;">world</span></div>,document.getElementById("app"),);

Implementation #

--- /dev/null+++ b/crank.js@@ -0,0 +1,99 @@+function wrap(value) {+ return value === undefined ? [] : Array.isArray(value) ? value : [value];+}++class Element {+ constructor(tag, props) {+ this.tag = tag;+ this.props = props;+ }+}++export const Portal = Symbol.for("crank.Portal");++export function createElement(tag, props, ...children) {+ props = Object.assign({}, props);+ if (children.length === 1) {+ props.children = children[0];+ } else if (children.length > 1) {+ props.children = children;+ }++ return new Element(tag, props);+}++export class Renderer {+ render(children, root) {+ const portal = createElement(Portal, {root}, children);+ return update(this, portal);+ }++ create(el) {+ return document.createElement(el.tag);+ }++ patch(el, node) {+ for (let [name, value] of Object.entries(el.props)) {+ if (name === "children") {+ continue;+ } else if (name === "class") {+ name = "className";+ }++ if (name in node) {+ node[name] = value;+ } else {+ node.setAttribute(name, value);+ }+ }+ }++ arrange(el, node, children) {+ let child = node.firstChild;+ for (const newChild of children) {+ if (child === newChild) {+ child = child.nextSibling;+ } else if (typeof newChild === "string") {+ if (child !== null && child.nodeType === Node.TEXT_NODE) {+ child.nodeValue = newChild;+ child = child.nextSibling;+ } else {+ node.insertBefore(document.createTextNode(newChild), child);+ }+ } else {+ node.insertBefore(newChild, child);+ }+ }++ while (child !== null) {+ const nextSibling = child.nextSibling;+ node.removeChild(child);+ child = child.nextSibling;+ }+ }+}++function update(renderer, el) {+ const values = [];+ for (const child of wrap(el.props.children)) {+ if (child instanceof Element) {+ values.push(update(renderer, child));+ } else if (child) {+ values.push(child);+ }+ }++ return commit(renderer, el, values);+}++function commit(renderer, el, values) {+ if (el.tag === Portal) {+ renderer.arrange(el, el.props.root, values);+ return undefined;+ }++ const node = renderer.create(el);+ renderer.patch(el, node);+ renderer.arrange(el, node, values);+ return node;+}

The createElement() function creates an Element instance which has two members, tag and props. The createElement() function’s main responsibility is to create an object for the element’s props if none are passed in, and to collect any remaining arguments under the name “children” on the props object.

The Element class should not be confused with the Element base class provided by the DOM. It’s an unfortunate name collision, but I also couldn’t bring myself to name the return value of a function named “createElement” anything else. These virtual elements are more or less plain JavaScript objects, and we only use a class to keep track of the element’s properties in one place. When referring to actual DOM nodes, we’ll use the term “node” in identifiers and properties instead.

As far as rendering goes, we’ve divided the process into the methods create(), patch() and arrange(), and the functions update() and commit(). Currently, we could probably inline all of this logic as a single function, but by using the power of hindsight I’ve structured the code so that we’ll mostly add to these functions as we implement more features.

The create(), patch() and arrange() methods are the only places in the module where we perform actual DOM operations. The create() method creates DOM nodes, the patch() method updates their properties and attributes, and the arrange() method manages the insertion and removal of DOM nodes. These methods are defined on the Renderer class because it’s possible that we might want to subclass it for custom DOM behavior, or to render to environments besides the DOM.

On the other hand, while we could have defined the update() and commit() functions as renderer methods as well, we make them functions private to the module because there will never be a need to expose them. We’ll see this technique for “method” privacy used more often later.

The update() and commit() functions represent the two phases of walking the element tree to create DOM nodes. The update() function walks the tree by calling update() recursively on each element child, collects the results of these calls in a values array, and calls the commit() function with this array of values. The commit() function is where the actual DOM mutations happen in the form of create(), patch(), and arrange() method calls. Finally, the update() and commit() functions return the created DOM nodes for each element so the same process can occur higher in the call stack.

Notes:

- In the

render()method, we create a specialPortalelement to serve as the root of the element tree. In Crank, aPortalis a special element tag which can be used to render into multiple user-provided DOM nodes at the same time. This can be helpful for use-cases such as tooltips or modals, and mirrors a similar API in React. Here, we mainly use it as a way to identify the root element so that we can call thearrange()method but not thecreate()orpatch()methods. The latter two methods wouldn’t make sense at the root. - In the

createElement()function, we unwrap the children array if it has a length of one, and don’t assign it if it has a length of zero. This is a theme we’ll see throughout the implementation, where we unwrap arrays of length zero or one just before we retain them in memory. The reason we do this is that if you look at a typical JSX tree, most of the elements in the tree will have zero or one children, so by not retaining this extra array we can save on runtime memory costs. When we need to actually iterate over thechildrenprop, we call the utility functionwrap()to create an array on the fly, so we don’t have to explicitly handle elements with zero or one children.

Step 2: Element Diffing #

Our renderer works, but will recreate every DOM node in the tree for every render. Not only is this inefficient but also incorrect, insofar as the renderer will reset stateful DOM nodes like form or media elements. We need a way to somehow preserve as much of the DOM as possible between renders.

Thankfully, we can diff entire trees efficiently because of an observation first made by the React authors, which is that for any two element subtrees, different root tags will usually indicate different substructures. For instance, a table element will almost certainly have different children as compared to a ul element. Therefore, we use an algorithm which recursively compares element tags at each level of the tree and throws away subtrees whose root tags don’t match.

Implementation #

--- a/crank.js+++ b/crank.js@@ -2,10 +2,20 @@ function wrap(value) {return value === undefined ? [] : Array.isArray(value) ? value : [value];}+function unwrap(arr) {+ return arr.length <= 1 ? arr[0] : arr;+}+class Element {constructor(tag, props) {this.tag = tag;this.props = props;++ this._node = undefined;+ this._children = undefined;++ // flags+ this._isMounted = false;}}@@ -22,78 +32,133 @@ export function createElement(tag, props, ...children) {return new Element(tag, props);}+function narrow(value) {+ if (typeof value === "boolean" || value == null) {+ return undefined;+ } else if (typeof value === "string" || value instanceof Element) {+ return value;+ }++ return value.toString();+}+export class Renderer {+ constructor() {+ this._cache = new WeakMap();+ }+render(children, root) {- const portal = createElement(Portal, {root}, children);+ let portal = this._cache.get(root);+ if (portal) {+ portal.props = {root, children};+ } else {+ portal = createElement(Portal, {root, children});+ this._cache.set(root, portal);+ }+return update(this, portal);}create(el) {return document.createElement(el.tag);}patch(el, node) {for (let [name, value] of Object.entries(el.props)) {if (name === "children") {continue;} else if (name === "class") {name = "className";}if (name in node) {node[name] = value;} else {node.setAttribute(name, value);}}}arrange(el, node, children) {let child = node.firstChild;for (const newChild of children) {if (child === newChild) {child = child.nextSibling;} else if (typeof newChild === "string") {if (child !== null && child.nodeType === Node.TEXT_NODE) {child.nodeValue = newChild;child = child.nextSibling;} else {node.insertBefore(document.createTextNode(newChild), child);}} else {node.insertBefore(newChild, child);}}while (child !== null) {const nextSibling = child.nextSibling;node.removeChild(child);child = child.nextSibling;}}}+function diff(renderer, oldChild, newChild) {+ if (+ oldChild instanceof Element &&+ newChild instanceof Element &&+ oldChild.tag === newChild.tag+ ) {+ if (oldChild !== newChild) {+ oldChild.props = newChild.props;+ newChild = oldChild;+ }+ }++ let value;+ if (newChild instanceof Element) {+ value = update(renderer, newChild);+ } else {+ value = newChild;+ }++ return [newChild, value];+}+function update(renderer, el) {+ if (el._isMounted) {+ el = createElement(el, {...el.props});+ }++ const oldChildren = wrap(el._children);+ const newChildren = wrap(el.props.children);+ const children = [];const values = [];- for (const child of wrap(el.props.children)) {- if (child instanceof Element) {- values.push(update(renderer, child));- } else if (child) {- values.push(child);+ const length = Math.max(oldChildren.length, newChildren.length);+ for (let i = 0; i < length; i++) {+ const oldChild = oldChildren[i];+ const newChild = narrow(newChildren[i]);+ const [child, value] = diff(renderer, oldChild, newChild);+ children.push(child);+ if (value) {+ values.push(value);}}+ el._children = unwrap(children);return commit(renderer, el, values);}function commit(renderer, el, values) {if (el.tag === Portal) {renderer.arrange(el, el.props.root, values);return undefined;+ } else if (!el._node) {+ el._node = renderer.create(el);}- const node = renderer.create(el);- renderer.patch(el, node);- renderer.arrange(el, node, values);- return node;+ renderer.patch(el, el._node);+ renderer.arrange(el, el._node, values);+ return el._node;}

To diff old and new trees, we need to retain old elements and DOM nodes so that we can make comparisons. At the renderer level, we use a weakmap to store the Portal elements we created in render() by the DOM node which we rendered into. At the element level, we store an element’s previously rendered children directly on the element under its _children property, and an element’s previously created DOM node under its _node property. We use leading underscores to indicate that these properties should be private to the module.

The diff() function compares old and new children by position, and if elements appear in the same position with the same tag, we simply copy the new element’s props over to the old element. Finally, in the commit() function, we check to see if an element has a DOM node defined on it before creating new ones.

Notes:

Element trees can contain almost any value:

true,false,nullandundefinedare erased, while numbers and non-element objects are converted to strings.const el = (<div>{"a"}{1 + 1}{true}{false}{null}{undefined}</div>);console.log(el.props.children); // ["a", 2, true, false, null, undefined]renderer.render(app);console.log(app.innerHTML); // <div>a2</div>Therefore, we use the helper function

narrow()to reduce the members of element trees to elements, strings, andundefined. This greatly simplifies the number of cases we need to handle when diffing.You might think mutating virtual elements directly is a little suspicious, as opposed to having some sort of separate internal node data structure. The fact is, most virtual elements which are created are thrown away every render, so retaining and mutating them is both more efficient and easier to implement, especially because any internal node type would have many of the same properties as elements anyways. Additionally, we can use a boolean flag (

_isMounted) to defensively clone elements if we ever detect that they’re being reused.

Step 3: Function Components #

The renderer can now efficiently create and mutate DOM nodes. However, we currently have to call the render() method with a full tree which looks more or less exactly like the HTML we want to render. The feature which makes JSX shine is that we can use the same syntax and diffing algorithm to encapsulate parts of the tree as components. To do this in Crank, we make the tags of elements reference a function rather than a string, and call that function with the element’s props when walking the element tree.

function Greeting({color, children}) {return (<div>Hello <span style={`color: ${color};`}>{children}</span></div>);}renderer.render(<Greeting color="red">World</Greeting>, app);

We use PascalCase when defining components because JSX transpilation is determined by the casing of the first letter of the tag: upper-case means the tag is an identifier in the current scope, and lower-case means the tag is a string.

Implementation #

--- a/crank.js+++ b/crank.js@@ -129,36 +129,45 @@ function diff(renderer, oldChild, newChild) {function update(renderer, el) {if (el._isMounted) {el = createElement(el, {...el.props});}const oldChildren = wrap(el._children);- const newChildren = wrap(el.props.children);+ let newChildren;+ if (typeof el.tag === "function") {+ newChildren = el.tag(el.props);+ } else {+ newChildren = el.props.children;+ }++ newChildren = wrap(newChildren);const children = [];const values = [];const length = Math.max(oldChildren.length, newChildren.length);for (let i = 0; i < length; i++) {const oldChild = oldChildren[i];const newChild = narrow(newChildren[i]);const [child, value] = diff(renderer, oldChild, newChild);children.push(child);if (value) {values.push(value);}}el._children = unwrap(children);return commit(renderer, el, values);}function commit(renderer, el, values) {- if (el.tag === Portal) {+ if (typeof el.tag === "function") {+ return unwrap(values);+ } else if (el.tag === Portal) {renderer.arrange(el, el.props.root, values);return undefined;} else if (!el._node) {el._node = renderer.create(el);}renderer.patch(el, el._node);renderer.arrange(el, el._node, values);return el._node;}

As you can see, implementing function components is relatively easy; when encountering tags which are functions, rather than recursing over the element’s children prop, we invoke the function with the element’s props and use the return value as the element’s children instead. This is why we will often refer to the return value of a function component as the component element’s “children.” As an additional note on terminology, we can now distinguish elements based on the type of their tag: we refer to elements with function tags as component elements, while we refer to elements which correspond to DOM nodes as host elements.

Using functions as tags meshes nicely with the element diffing algorithm, insofar as different functions are likely to produce different child structures.

Step 4: Iterables and Fragments #

Here, we’ll take a slight detour in our implementation of components to handle iterables in the element tree. Crank allows any collection which implements the iterable interface to be rendered as well. To review, an iterable is any JavaScript object which implements a [Symbol.iterator]() method. This includes arrays, sets, and any other data structure which you can iterate over using a for…of statement.

Currently, our module converts these data structures to strings using their toString method, but what we really want is to diff and render their contents recursively.

const arr = [1, 2, 3];const set = new Set(["a", "b", "c"]);renderer.render(<div>{arr} {set}</div>,app,);console.log(app.innerHTML);// Expected: "<div>123 abc</div>"// Actual: "<div>1,2,3 [object Set]</div>"

Iterables can appear anywhere in the element tree: as the child of a host element, as the return value of a component, or even nested in another iterable. Therefore, the easiest way to implement this feature is to treat every iterable we find in the element tree as though it were an element itself. To achieve this, we define a special element tag Fragment, and whenever we find an iterable, we wrap it in a Fragment element using a createElement call, with the iterable as the element’s children.

One added benefit of this approach is that we can use the Fragment tag directly, by referencing the tag like a component, or by using JSX’s special fragment syntax (<>{children}</>) with the proper transpiler configuation.

// explicit referencerenderer.render(<Fragment><div>1</div><div>2</div></Fragment>,app,);console.log(document.body.innerHTML); // "<div>1</div><div>2</div>"// JSX fragment syntaxrenderer.render(<><div>1</div><div>2</div></>,app,);console.log(document.body.innerHTML); // "<div>1</div><div>2</div>"

Implementation #

--- a/crank.js+++ b/crank.js@@ -6,6 +6,14 @@ function unwrap(arr) {return arr.length <= 1 ? arr[0] : arr;}+function arrayify(value) {+ return value == null+ ? []+ : typeof value !== "string" && typeof value[Symbol.iterator] === "function"+ ? Array.from(value)+ : [value];+}+class Element {constructor(tag, props) {this.tag = tag;@@ -21,6 +29,8 @@ class Element {export const Portal = Symbol.for("crank.Portal");+export const Fragment = "";+export function createElement(tag, props, ...children) {props = Object.assign({}, props);if (children.length === 1) {@@ -35,13 +45,55 @@ export function createElement(tag, props, ...children) {function narrow(value) {if (typeof value === "boolean" || value == null) {return undefined;} else if (typeof value === "string" || value instanceof Element) {return value;+ } else if (typeof value[Symbol.iterator] === "function") {+ return createElement(Fragment, null, value);}return value.toString();}+function normalize(values) {+ const values1 = [];+ let buffer;+ for (const value of values) {+ if (!value) {+ // pass+ } else if (typeof value === "string") {+ buffer = (buffer || "") + value;+ } else if (!Array.isArray(value)) {+ if (buffer) {+ values1.push(buffer);+ buffer = undefined;+ }++ values1.push(value);+ } else {+ for (const value1 of value) {+ if (!value1) {+ // pass+ } else if (typeof value1 === "string") {+ buffer = (buffer || "") + value1;+ } else {+ if (buffer) {+ values1.push(buffer);+ buffer = undefined;+ }++ values1.push(value1);+ }+ }+ }+ }++ if (buffer) {+ values1.push(buffer);+ }++ return values1;+}+export class Renderer {constructor() {this._cache = new WeakMap();@@ -129,45 +181,45 @@ function diff(renderer, oldChild, newChild) {function update(renderer, el) {if (el._isMounted) {el = createElement(el, {...el.props});}const oldChildren = wrap(el._children);let newChildren;if (typeof el.tag === "function") {newChildren = el.tag(el.props);} else {newChildren = el.props.children;}- newChildren = wrap(newChildren);+ newChildren = arrayify(newChildren);const children = [];const values = [];const length = Math.max(oldChildren.length, newChildren.length);for (let i = 0; i < length; i++) {const oldChild = oldChildren[i];- const newChild = narrow(newChildren[i]);+ let newChild = narrow(newChildren[i]);const [child, value] = diff(renderer, oldChild, newChild);children.push(child);if (value) {values.push(value);}}el._children = unwrap(children);- return commit(renderer, el, values);+ return commit(renderer, el, normalize(values));}function commit(renderer, el, values) {- if (typeof el.tag === "function") {+ if (typeof el.tag === "function" || el.tag === Fragment) {return unwrap(values);} else if (el.tag === Portal) {renderer.arrange(el, el.props.root, values);return undefined;} else if (!el._node) {el._node = renderer.create(el);}renderer.patch(el, el._node);renderer.arrange(el, el._node, values);return el._node;}

To implement fragments, we adjust the narrow function so that any time a non-string iterable is detected we wrap it in a createElement call. We need to be careful to exclude strings from our iterable detection logic. Strings are iterable but we don’t want to iterate over them because we would end up diffing each string found in the element tree character by character, which would be inefficient.

Notes:

- We define the helper function

normalize(), which is similar to the DOM’sNode.prototype.normalize()method. It is called on thevaluesarray in theupdate()function, and will shallowly flatten the array, as well as concatenate adjacent strings and remove anyundefinedvalues. This is what allows arrays of values to be returned from theupdate()andcommit()functions, as would happen in the case ofFragmentelements. We only need to flatten the array shallowly becausenormalize()is called at each level of the element tree. - We also define another helper function

arrayify(), which basically does the same thing aswrap()but handles iterables. - In Crank, the

Fragmenttag is actually just the empty string. I believe that every JSX framework/library could make theirFragmentequivalent the empty string without any major changes to their codebase or API. The empty string makes the most sense as the default for JSX fragment syntax, and adopting this convention would lessen configuration overhead for developers.

Step 5: Generator Components #

We now have basic rendering and components, but components need to do more than just group parts of the element tree; nowadays, we expect any component abstraction to be able to encapsulate state, so that we can write components which respond to user input or timers, for instance.

In Crank, we use generator functions to write stateful components. As a quick review, generator functions are a separate function syntax which adds a star after the function keyword (function *). Inside a generator function, you can not only return values but also yield values as well using the yield operator.

function *fibonacci() {let current = 0, next = 1;while (true) {yield current;[current, next] = [next, current + next];}}const iter = fib();// Nothing happens yet because we haven’t used the iterator.const arr = [];for (const n of iter) {if (n > 30) {break;}arr.push(n);}console.log(arr); // [0, 1, 1, 2, 3, 5, 8, 13, 21]

This example, which defines and calls a fibonacci number generator function, demonstrates some important qualities of generator functions.

Generator functions execute lazily. Calling a generator function does not execute its body; rather, it returns a generator object. Until this object is somehow used, the generator function does not run.

Generator functions can model infinite sequences. If we didn’t include the

breakstatement in the loop over the generator object, this program would never terminate because thefibonacci()function never returns.Generator functions can hold internal state. The

currentandnextvariables are local to the generator function’s scope, and are preserved between iterations.

Crank takes advantage of all three of these features by allowing components to be written as generator functions which yield element trees. By retaining generator objects just like we retained DOM nodes and children, we can preserve the local scope of the generator for component elements.

function *Counter() {let i = 0;while (true) {yield (<div>Rendered {i++} time(s)</div>);}}renderer.render(<Counter />, app);renderer.render(<Counter />, app);renderer.render(<Counter />, app);console.log(app.innerHTML); // <div>Rendered 2 time(s)</div>

Iterables vs Iterators #

Before we dive into the code, we need to make a distinction between iterables and iterators. As explained previously, an iterable is any object which implements the [Symbol.iterator]() method. On the other hand, an iterator is any object which implements a next() method, and optionally return() and throw() methods. To conform to the iterator interface, these methods must return iterations, objects which have value and done properties, with done being a boolean which indicates whether the iterator has returned.

const iter = fibonacci();console.log(iter.next()); // {value: 0, done: false}console.log(iter.next()); // {value: 1, done: false}console.log(iter.next()); // {value: 1, done: false}console.log(iter.next()); // {value: 2, done: false}

Iterables and iterators are related in that the [Symbol.iterator]() method must return an iterator. This means that you can trivially make any iterator iterable by adding a [Symbol.iterator]() method to it which returns this. The for…of statement uses the [Symbol.iterator]() method under the hood, so the following two code snippets are roughly equivalent.

for (const n of fibonacci()) {if (n > 30) {break;}console.log(n);}// is roughly equivalent to:const iterator = fibonacci()[Symbol.iterator]();let iteration = iterator.next();try {while (!iteration.done) {const n = iteration.value;if (n > 30) {break;}console.log(n);}} finally {if (!iteration.done && iterator.return) {iterator.return();}}

Generator objects implement both the iterable and iterator interfaces; in other words, generator objects are iterable iterators. This means you can both use generator objects in for…of loops, and also call the iterator methods directly. We’ll do the latter, because this approach is more flexible.

Implementation #

--- a/crank.js+++ b/crank.js@@ -14,15 +14,20 @@ function arrayify(value) {: [value];}+function isIteratorLike(value) {+ return value != null && typeof value.next === "function";+}+class Element {constructor(tag, props) {this.tag = tag;this.props = props;this._node = undefined;this._children = undefined;+ this._ctx = undefined;// flagsthis._isMounted = false;}}@@ -181,30 +186,35 @@ function diff(renderer, oldChild, newChild) {function update(renderer, el) {if (el._isMounted) {el = createElement(el, {...el.props});}- const oldChildren = wrap(el._children);- let newChildren;if (typeof el.tag === "function") {- newChildren = el.tag(el.props);- } else {- newChildren = el.props.children;+ if (!el._ctx) {+ el._ctx = new Context(renderer, el);+ }++ return updateCtx(el._ctx);}+ return updateChildren(renderer, el, el.props.children);+}++function updateChildren(renderer, el, newChildren) {+ const oldChildren = wrap(el._children);newChildren = arrayify(newChildren);const children = [];const values = [];const length = Math.max(oldChildren.length, newChildren.length);for (let i = 0; i < length; i++) {const oldChild = oldChildren[i];let newChild = narrow(newChildren[i]);const [child, value] = diff(renderer, oldChild, newChild);children.push(child);if (value) {values.push(value);}}el._children = unwrap(children);return commit(renderer, el, normalize(values));}@@ -223,3 +233,29 @@ function commit(renderer, el, values) {renderer.arrange(el, el._node, values);return el._node;}++class Context {+ constructor(renderer, el) {+ this._renderer = renderer;+ this._el = el;+ this._iter = undefined;+ }+}++function updateCtx(ctx) {+ if (!ctx._iter) {+ const value = ctx._el.tag(ctx._el.props);+ if (isIteratorLike(value)) {+ ctx._iter = value;+ } else {+ return updateCtxChildren(ctx, value);+ }+ }++ const iteration = ctx._iter.next();+ return updateCtxChildren(ctx, iteration.value);+}++function updateCtxChildren(ctx, children) {+ return updateChildren(ctx._renderer, ctx._el, narrow(children));+}

In this step, we’ve encapsulated the execution of components in a helper class called the Context. This will be where we store all state which is required to execute component functions from now on. So far, we’ve stored the renderer, the element, and any iterator returned by the component, directly on this context class.

We could also try to retain this state directly on component elements, but by storing them on contexts, we indirectly reduce the size of elements themselves. In a typical application, the number of host elements might exceed the number of component elements by 10:1, so it makes sense to put component-specific data in its own abstraction.

To detect generator components, we check that the return value of the component is “iterator-like,” which just means that it is an object which defines a next() method. Although generators are both iterators and iterable, we check for the iterator interface, because, as explained previously, we interpret iterables as fragments wherever they appear in the element tree. If we determined any component which returns an iterable was also a generator component, we would get suprising behavior where the following component renders the strings "a", "b" and "c" in successive renders, rather than all at once as siblings.

function Component() {return ["a", "b", "c"];}

While there may be ways to distinguish generator functions from normal functions without calling them, doing so is an anti-pattern because it precludes components which return generator objects from being generator components. This theme of inspecting the return values of component functions to determine their type will continue as we implement more component types.

Notes:

- We divided the

update()function intoupdate()andupdateChildren(), and created analogous functionsupdateCtx()andupdateCtxChildren()for component contexts. These functions use the “private method” pattern described previously. TheupdateCtxChildren()function is primarily used so that we can wrap yielded/returned children in anarrow()call for diffing purposes.

Step 6: Refreshing #

We now have stateful components via generators, but these generator functions only rerender based on top-level render() calls. To write interactive components, we need a way for components to rerender themselves. In Crank, we pass in the context object we created in the previous step as the this value of component functions, and implement a refresh() method on it which re-executes the component. This allows us to write components like the following.

function *Counter() {let i = 0;const onclick = () => {i++;this.refresh();};while (true) {yield (<button onclick={onclick}>Button pressed {i} time(s).</button>);}}

We’ve already implemented basic event handling thanks to the DOM’s onevent handlers and the logic in the renderer’s patch() method, so all we need to do is pass the context in as this using Function.prototype.call and implement the refresh() method on the context class.

Implementation #

--- a/crank.js+++ b/crank.js@@ -237,21 +237,25 @@ function commit(renderer, el, values) {class Context {constructor(renderer, el) {this._renderer = renderer;this._el = el;this._iter = undefined;}++ refresh() {+ return updateCtx(this);+ }}function updateCtx(ctx) {if (!ctx._iter) {- const value = ctx._el.tag(ctx._el.props);+ const value = ctx._el.tag.call(ctx, ctx._el.props);if (isIteratorLike(value)) {ctx._iter = value;} else {return updateCtxChildren(ctx, value);}}const iteration = ctx._iter.next();return updateCtxChildren(ctx, iteration.value);}

After Crank’s release, multiple people objected to this unusual usage of this. As an alternative to using this, some suggested passing the context in directly as a parameter. There are many reasons why I think using this is the best choice for component API design, and I’ll outline a few of them here.

Using

thismakes it harder for developers to call components directly. As we’ve seen so far, components can either return children or an iterator which yields children. Because both these cases need to be handled, we need to take care to make sure that people don’t call components directly. Additionally, direct calls of components is an anti-pattern even if you know the component is a regular function which returns elements, because as we’ve learned, we use the functions themselves to identify subtrees for our diffing algorithm. Passing contexts in asthisis a natural barrier which prevents developers from attempting to call components directly, insofar as you would need to use theFunction.prototype.call()method.Using

thismakes it harder for developers to destructure the context. If we passed the context in as a parameter, there would always be a chance for developers to destructure the context parameter just as they destructured props.// Destructuring the proposed context parameter.function *MyComponent({myProp}, {refresh}) {/* … */const onclick = () => {/* … */refresh();};/* … */}To make this example work, we would either need to eagerly bind the

refresh()method to the context, or alternatively define therefresh()method as a function which references the context in a closure. In either case, we would need to create a uniquerefresh()function for every component instance, which would increase the memory requirements for each component. Even worse, this would have to be done for every single method we wanted to define on the context. Insofar as destructuringthiswould require an extra line of code, its usage again provides a natural barrier which prevents developers from destructuring contexts and inadvertently losing method receivers.Components are a special construct which are somewhere between a class and a function. While all components in Crank are defined with functions, we need a way to define “instance” methods and properties like

refresh()and have them available within component declarations. I like to reference this tweet thread by React maintainer Dan Abramov, about components as an abstraction. He writes:React is traditionally described either in FP terms (pure functions) or in OOP terms (stateful classes). Both are only approximations … Why are these models insufficient to describe React? “Pure function” model doesn’t describe local state which is an essential React feature. “Class” model doesn’t explain pure-ish render, disawoving inheritance, lack of direct instantiation, and “receiving” props …

What is a component? … It’s a thing of its own. A stateful function with effects. Your language just doesn’t have a primitive to express it.

Abramov goes on to use this observation to justify React hooks, whereas of course, I would use the same line of reasoning to justify the usage of generator functions. Nevertheless, I think the observations he makes are valid, and that neither functions nor classes alone fully capture what we want from a component abstraction.

Calling component functions with

thisset to a framework-provided context object is a great way to model this half-function, half-class quality of components. It provides both the convenience of inheritance and the terseness of function declarations, and captures the uniqueness of component abstractions in a way which is still “just JavaScript.”

There are of course other reasons for and against using the this value as the context in components. At its root, I believe most arguments against using this are driven by a desire to define all functions as top-level arrow function assignments (const MyComponent = (props) => ). While I don’t think I’ll be able to convince people of the benefit of one or the other style of coding in the general case, hopefully I’ve convinced you as to why using this like we do in Crank might make sense for a component framework.

A second controversial design decison was the usage of explicit refresh() calls rather than some kind of “reactive” setState()- or proxy-based system. I will probably write another essay at some point explaining why I think explicit, opt-in rerendering is preferable to any other system for a component framework, but for now, note that it’s easier to implement: the refresh() method is currently a one-liner!

Step 7: Rearranging #

Our generator components have a subtle bug which we need to fix before continuing. Components which render different roots on refresh will not rerender. For instance, the following component should cycle rendering h1 through h6 elements when clicked.

function *CyclingHeader({name}) {let i = 0;const onclick = () => {i = (i + 1) % 6;this.refresh();};while (true) {const Header = `h${i + 1}`;yield (<Header onclick={onclick}>Heading level {i + 1}</Header>);}}renderer.render(<div><CyclingHeader /></div>,app,);app.firstChild.click();app.firstChild.click();console.log(app.innerHTML);// Expected: <div><h3>Heading level 3</h3></div>// Actual: <div><h1>Heading level 1</h1></div>

If you run this component, you’ll notice that clicking on the header doesn’t actually do anything. The problem is that we haven’t called the arrange() method on the component’s nearest ancestor host element. We can confirm that this is the cause of the bug by wrapping the component’s yield value in an extra div element. In that case, rendering would work correctly because arrange() is called on all of a component’s children for each refresh.

Implementation #

--- a/crank.js+++ b/crank.js@@ -99,167 +99,216 @@ function normalize(values) {return values1;}+function getValue(el) {+ if (el.tag === Portal) {+ return undefined;+ } else if (typeof el.tag !== "function" && el.tag !== Fragment) {+ return el._node;+ }++ return unwrap(getChildValues(el));+}++function getChildValues(el) {+ const values = [];+ for (const child of wrap(el._children)) {+ if (typeof child === "string") {+ values.push(child);+ } else if (typeof child !== "undefined") {+ values.push(getValue(child));+ }+ }++ return normalize(values);+}+export class Renderer {constructor() {this._cache = new WeakMap();}render(children, root) {let portal = this._cache.get(root);if (portal) {portal.props = {root, children};} else {portal = createElement(Portal, {root, children});this._cache.set(root, portal);}- return update(this, portal);+ return update(this, portal, portal);}create(el) {return document.createElement(el.tag);}patch(el, node) {for (let [name, value] of Object.entries(el.props)) {if (name === "children") {continue;} else if (name === "class") {name = "className";}if (name in node) {node[name] = value;} else {node.setAttribute(name, value);}}}arrange(el, node, children) {let child = node.firstChild;for (const newChild of children) {if (child === newChild) {child = child.nextSibling;} else if (typeof newChild === "string") {if (child !== null && child.nodeType === Node.TEXT_NODE) {child.nodeValue = newChild;child = child.nextSibling;} else {node.insertBefore(document.createTextNode(newChild), child);}} else {node.insertBefore(newChild, child);}}while (child !== null) {const nextSibling = child.nextSibling;node.removeChild(child);child = child.nextSibling;}}}-function diff(renderer, oldChild, newChild) {+function diff(renderer, host, oldChild, newChild) {if (oldChild instanceof Element &&newChild instanceof Element &&oldChild.tag === newChild.tag) {if (oldChild !== newChild) {oldChild.props = newChild.props;newChild = oldChild;}}let value;if (newChild instanceof Element) {- value = update(renderer, newChild);+ value = update(renderer, host, newChild);} else {value = newChild;}return [newChild, value];}-function update(renderer, el) {+function update(renderer, host, el) {if (el._isMounted) {el = createElement(el, {...el.props});}if (typeof el.tag === "function") {if (!el._ctx) {- el._ctx = new Context(renderer, el);+ el._ctx = new Context(renderer, host, el);}return updateCtx(el._ctx);+ } else if (el.tag !== Fragment) {+ host = el;}- return updateChildren(renderer, el, el.props.children);+ return updateChildren(renderer, host, el, el.props.children);}-function updateChildren(renderer, el, newChildren) {+function updateChildren(renderer, host, el, newChildren) {const oldChildren = wrap(el._children);newChildren = arrayify(newChildren);const children = [];const values = [];const length = Math.max(oldChildren.length, newChildren.length);for (let i = 0; i < length; i++) {const oldChild = oldChildren[i];let newChild = narrow(newChildren[i]);- const [child, value] = diff(renderer, oldChild, newChild);+ const [child, value] = diff(renderer, host, oldChild, newChild);children.push(child);if (value) {values.push(value);}}el._children = unwrap(children);return commit(renderer, el, normalize(values));}function commit(renderer, el, values) {- if (typeof el.tag === "function" || el.tag === Fragment) {+ if (typeof el.tag === "function") {+ return commitCtx(el._ctx, values);+ } else if (el.tag === Fragment) {return unwrap(values);} else if (el.tag === Portal) {renderer.arrange(el, el.props.root, values);return undefined;} else if (!el._node) {el._node = renderer.create(el);}renderer.patch(el, el._node);renderer.arrange(el, el._node, values);return el._node;}class Context {- constructor(renderer, el) {+ constructor(renderer, host, el) {this._renderer = renderer;+ this._host = host;this._el = el;this._iter = undefined;++ // flags+ this._isUpdating = false;}refresh() {- return updateCtx(this);+ return stepCtx(this);}}-function updateCtx(ctx) {+function stepCtx(ctx) {if (!ctx._iter) {const value = ctx._el.tag.call(ctx, ctx._el.props);if (isIteratorLike(value)) {ctx._iter = value;} else {return updateCtxChildren(ctx, value);}}const iteration = ctx._iter.next();return updateCtxChildren(ctx, iteration.value);}+function updateCtx(ctx) {+ ctx._isUpdating = true;+ return stepCtx(ctx);+}+function updateCtxChildren(ctx, children) {- return updateChildren(ctx._renderer, ctx._el, narrow(children));+ return updateChildren(ctx._renderer, ctx._host, ctx._el, narrow(children));+}++function commitCtx(ctx, values) {+ if (!ctx._isUpdating) {+ ctx._renderer.arrange(+ ctx._host,+ ctx._host.tag === Portal ? ctx._host.props.root : ctx._host._node,+ getChildValues(ctx._host),+ );+ }++ ctx._isUpdating = false;+ return unwrap(values);}

This diff is larger because we have to adjust the signatures of many of the recursive renderer functions we’ve defined, adding a parameter for the current host element and passing it down the tree. With this data available, we can now retain it on component contexts, so that it can be accessed by context methods and functions. We also add an _isUpdating boolean flag to contexts, to help us determine whether a component is being updated by a parent or doing a self-initiated refresh. Finally, we create a commitCtx() function, analogous to the commit() renderer function, which calls arrange() on a component’s nearest ancestor host element if the component is detected as refreshing.

Notes:

We’ve added the utility functions

getValue()andgetChildValues(). These mutually recursive functions traverse the element tree and find an element’s value or child values. The “value” of an element varies based on its tag; a host element’s value is just the DOM node which we created for it, while a component or fragment element’s value can beundefined, a string, a DOM node, or array of strings and DOM nodes, depending on the element’s children.We were previously using the return values of the

update()andcommit()functions to pass element values upwards, but when we rearrange a host element, we don’t have access to the host element’s child values, because that host element may have other children besides the component which is refreshing. Therefore, we usegetChildValuesto compute a host element’s child values on the fly when rearranging to save on memory.We’ve moved most of the logic in the

updateCtx()function to thestepCtx()function. BothupdateCtx()and therefresh()method callstepCtx(), but onlyupdateCtx()sets the_isUpdatingflag. We could also have named the flag “_isRefreshing” and set it in therefresh()method, but setting the flag by updates is more convenient for when we deal with concurrent async rendering situations later on.

Step 8: Returning and Unmounting #

One of the coolest features of generator functions is that they can be closed at both ends: internally, a return statement may be placed in the generator’s body to end its iteration, and externally, the iterator method return() can be called on the generator object.

To review, the return() method will close a generator execution by replacing the currently suspended yield with a return operation. This means that any loops the generator was in would be broken out of, and code which would normally execute after the yield would never execute.

We can take advantage of the return() method by calling it on component iterators when their corresponding elements are removed from the element tree. This in turn allows developers to write cleanup code by wrapping yield operations in a try/finally-statement, as in the following component.

function *Timer() {let seconds = 0;const interval = setInterval(() => {seconds++;this.refresh();}, 1000);try {while (true) {yield <div>Seconds: {seconds}</div>;}} finally {clearInterval(interval);}}

Currently, the clearInterval() call will never be reached, and would cause a memory leak if the component were rendered and removed multiple times.

Implementation #

--- a/crank.js+++ b/crank.js@@ -227,20 +227,30 @@ function update(renderer, host, el) {function updateChildren(renderer, host, el, newChildren) {const oldChildren = wrap(el._children);newChildren = arrayify(newChildren);const children = [];const values = [];const length = Math.max(oldChildren.length, newChildren.length);for (let i = 0; i < length; i++) {const oldChild = oldChildren[i];let newChild = narrow(newChildren[i]);const [child, value] = diff(renderer, host, oldChild, newChild);+ if (oldChild instanceof Element && child !== oldChild) {+ unmount(renderer, oldChild);+ }+children.push(child);if (value) {values.push(value);}}el._children = unwrap(children);+ for (const oldChild of oldChildren.slice(length)) {+ if (oldChild instanceof Element) {+ unmount(renderer, oldChild);+ }+ }+return commit(renderer, el, normalize(values));}@@ -261,33 +271,52 @@ function commit(renderer, el, values) {return el._node;}+function unmount(renderer, el) {+ if (typeof el.tag === "function") {+ unmountCtx(el._ctx);+ }++ for (const child of wrap(el._children)) {+ if (child instanceof Element) {+ unmount(renderer, child);+ }+ }+}+class Context {constructor(renderer, host, el) {this._renderer = renderer;this._host = host;this._el = el;this._iter = undefined;// flagsthis._isUpdating = false;+ this._isDone = false;}refresh() {return stepCtx(this);}}function stepCtx(ctx) {- if (!ctx._iter) {+ if (ctx._isDone) {+ return getValue(ctx._el);+ } else if (!ctx._iter) {const value = ctx._el.tag.call(ctx, ctx._el.props);if (isIteratorLike(value)) {ctx._iter = value;} else {return updateCtxChildren(ctx, value);}}const iteration = ctx._iter.next();+ if (iteration.done) {+ ctx._isDone = true;+ }+return updateCtxChildren(ctx, iteration.value);}@@ -312,3 +341,12 @@ function commitCtx(ctx, values) {ctx._isUpdating = false;return unwrap(values);}++function unmountCtx(ctx) {+ if (!ctx._isDone) {+ ctx._isDone = true;+ if (ctx._iterator && typeof ctx._iterator.return === "function") {+ ctx._iterator.return();+ }+ }+}

We’ve added another renderer function, unmount, along with its analogous context function, unmountCtx. It is important to make the unmount function recursive, because there can be component elements deeply nested in the element tree which expect to be returned.

We’ve also added the flag _isDone to context objects to keep track of the iterator’s current state. By checking the done property for each iteration, we can freeze generator components on their final rendered values if they are detected as having returned.

function MyComponent() {yield 1;yield 2;return 3;}renderer.render(<MyComponent />, app);console.log(app.innerHTML); // 1renderer.render(<MyComponent />, app);console.log(app.innerHTML); // 2renderer.render(<MyComponent />, app);console.log(app.innerHTML); // 3renderer.render(<MyComponent />, app);console.log(app.innerHTML); // 3

When a generator function is returned before it is unmounted, this usually indicates programmer error, so sticking to its final value will make the sitution more obvious to the developer. Thanks to the getValue function implemented in the previous step, it’s now easy to get the final rendered value of a returned generator component element.

Step 9: Props Iterators #

The generator components we’ve seen so far haven’t referenced the props parameter in any way; we have exclusively used generator functions which take no parameters and yield elements in a while (true) loop. Eventually though, we’ll want to write generator functions which use props just like any other component. However, we cannot simply reference the props parameter as for regular function components, because for generator functions, the props parameter may not necessarily reflect the latest props passed to the component.

There were potentially many ways to solve this problem. The design I chose for Crank was to make the context object an iterable of the component’s props, so that you could again destructure props in a for…of loop over this.

function *StatefulGreeting({color, name}) {let prevName;for ({color, name} of this) {yield (<div>Hello {prevName === name && "again, "}<span style={`color: ${color};`}>{name}</span></div>);prevName = name;}}

This was yet another of the more controversial design decisions for Crank, likely because it combines multiple syntaxes and keywords in an unusual way. Seeing for…of, object destructuring, and this all in the same line of code might have been too much for some people. Hopefully, by this point, I’ve explained enough of iterators and iterables, as well as why we use this, that this pattern doesn’t overwhelm you.

My reasons for choosing this design is that it allows developers to make the common refactoring of stateless function components to stateful generator components in the fewest keystrokes: you copy the props parameter into a this loop header, move the function body into the loop, and replace return keywords with yield keywords. Additionally, because new props are just variable assignments, we can compare old and new props easily, blending the concepts of props and state, as in the above example.

Ultimately, I didn’t want to diverge too much from the typical function component syntax, where the first parameter is the props of the component, and is usually destructured inline. This syntax makes it easy to understand what props a component expects by having it defined at the top of the function. Furthermore, TypeScript’s JSX type-checking feature for function components continues to work based on the props parameter, even if the function is a generator function.

Implementation #

--- a/crank.js+++ b/crank.js@@ -286,36 +286,49 @@ function unmount(renderer, el) {class Context {constructor(renderer, host, el) {this._renderer = renderer;this._host = host;this._el = el;this._iter = undefined;// flagsthis._isUpdating = false;+ this._isIterating = false;this._isDone = false;}refresh() {return stepCtx(this);}++ *[Symbol.iterator]() {+ while (!this._isDone) {+ if (this._isIterating) {+ throw new Error("Context iterated twice without a yield");+ }++ this._isIterating = true;+ yield this._el.props;+ }+ }}function stepCtx(ctx) {if (ctx._isDone) {return getValue(ctx._el);} else if (!ctx._iter) {const value = ctx._el.tag.call(ctx, ctx._el.props);if (isIteratorLike(value)) {ctx._iter = value;} else {return updateCtxChildren(ctx, value);}}const iteration = ctx._iter.next();+ ctx._isIterating = false;if (iteration.done) {ctx._isDone = true;}return updateCtxChildren(ctx, iteration.value);}

Notes:

- The

[Symbol.iterator]()method is a generator method. The syntax is similar to function generators in that we use a star, except now the star appears before the method name. Additionally, we use computed method syntax (the square brackets) so that we can reference the globalSymbol.iteratorsymbol. - We add an

_isIteratingflag to contexts to detect when props are pulled multiple times without a yield, so that we can throw an error. This would happen if the developer forgot to yield from within the for loop. Throwing an error provides predictable feedback as opposed to entering an infinite loop.

Step 10: Accessing DOM Nodes #

You may have noticed that the refresh() method already returns the actual DOM node or nodes which components render. One of the goals of Crank is to be a framework which makes it easy to do raw DOM operations. For many use-cases, it’s just easier to get your hands dirty and mutate the DOM by hand, even if you still want to use components and virtual elements for most situations. To that extent, we’ll add some more ways for users to access DOM nodes.

First, we’ll take advantage of an advanced feature of generator functions. The next() method of generator objects can optionally take an argument which will be “passed into” the generator as the result of the yield operation. For example, we can elaborate on the fibonacci number generator we saw previously by allowing the caller to pass in a truthy value to reset the sequence.

function *fibonacci() {let current = 0, next = 1;while (true) {const reset = yield current;if (reset) {[current, next] = [0, 1];} else {[current, next] = [next, current + next];}}}const iter = fibonacci();console.log(iter.next()); // {value: 0, done: false}console.log(iter.next()); // {value: 1, done: false}console.log(iter.next()); // {value: 1, done: false}console.log(iter.next()); // {value: 2, done: false}console.log(iter.next(true)); // {value: 0, done: false}console.log(iter.next()); // {value: 1, done: false}

The reset variable is set to the yield operation, and we reset the current and next variables if reset is detected as truthy. This feature of generator functions only works when calling the iterator methods; when using for…of loops, the yield operation will always resolve to undefined.

For Crank, the most natural thing to pass back into generator components is the DOM nodes which were rendered. This gives generator components a “call and response”-like structure, where the generator yields virtual elements and gets their realized equivalents passed back in.

function *ImperativeCounter() {let i = 0;let button;for ({} of this) {if (button) {/* do whatever DOM mutations you please */button.style.color = "red";}i++;button = yield <button>{i}</button>;}}

This API is intuitive, but doesn’t work too well with sync generator components, insofar as generator functions suspend directly on the yield keyword. While the yield operation can be assigned to a local variable, the actual timing of the assignment might surprise developers, insofar as it wouldn’t happen until the generator component was rerendered. In this case, any callbacks which expect the variable to have already been assigned would error.

function *ImperativeCounter() {let i = 0;let button;const onclick = () => {// button may not be assigned after the first renderbutton.style.color = "red";i++;this.refresh();}for ({} of this) {button = yield <button>{i}</button>;}}

As we’ll see later, this is less of a problem for async generator components, which resume continuously when mounted, but for sync generator components we’ll implement another context method schedule() to make yield values more useful. The schedule() method takes a callback which fires once when the component has committed. It allows us to write components like the following.

function *ImperativeCounter() {let i = 0;let button;const onclick = () => {i++;button.style.color = "red";this.refresh();};this.schedule(() => this.refresh());for ({} of this) {button = yield <button onclick={onclick}>{i}</button>;}}

The schedule method can be used to listen for component commits more generally, but here we use it to trigger a second synchronous execution of the ImperativeCounter component the first time it is rendered. We do this by pairing it with the refresh method. In the example, generator resumes a second time synchronously, so the button variable is always available in the closure of the onclick callback.

Second, we’ll also change the return value of the render() method slightly so that the created Portal element’s child values are returned, whereas before we returned undefined. In Crank, the value of a Portal is always undefined, so that the parents of the portal do not attempt to insert the Portal element’s root into the DOM in unexpected places. By returning the portal’s child values, we can make the render() method’s return value a little more useful.

Implementation #

--- a/crank.js+++ b/crank.js@@ -125,61 +125,62 @@ function getChildValues(el) {export class Renderer {constructor() {this._cache = new WeakMap();}render(children, root) {let portal = this._cache.get(root);if (portal) {portal.props = {root, children};} else {portal = createElement(Portal, {root, children});this._cache.set(root, portal);}- return update(this, portal, portal);+ update(this, portal, portal);+ return getChildValues(portal);}create(el) {return document.createElement(el.tag);}patch(el, node) {for (let [name, value] of Object.entries(el.props)) {if (name === "children") {continue;} else if (name === "class") {name = "className";}if (name in node) {node[name] = value;} else {node.setAttribute(name, value);}}}arrange(el, node, children) {let child = node.firstChild;for (const newChild of children) {if (child === newChild) {child = child.nextSibling;} else if (typeof newChild === "string") {if (child !== null && child.nodeType === Node.TEXT_NODE) {child.nodeValue = newChild;child = child.nextSibling;} else {node.insertBefore(document.createTextNode(newChild), child);}} else {node.insertBefore(newChild, child);}}while (child !== null) {const nextSibling = child.nextSibling;node.removeChild(child);child = child.nextSibling;}}}@@ -286,49 +287,56 @@ function unmount(renderer, el) {class Context {constructor(renderer, host, el) {this._renderer = renderer;this._host = host;this._el = el;this._iter = undefined;+ this._schedules = new Set();// flagsthis._isUpdating = false;this._isIterating = false;this._isDone = false;}refresh() {return stepCtx(this);}+ schedule(callback) {+ this._schedules.add(callback);+ }+*[Symbol.iterator]() {while (!this._isDone) {if (this._isIterating) {throw new Error("Context iterated twice without a yield");}this._isIterating = true;yield this._el.props;}}}function stepCtx(ctx) {+ let initial = !ctx._iter;if (ctx._isDone) {return getValue(ctx._el);- } else if (!ctx._iter) {+ } else if (initial) {const value = ctx._el.tag.call(ctx, ctx._el.props);if (isIteratorLike(value)) {ctx._iter = value;} else {return updateCtxChildren(ctx, value);}}- const iteration = ctx._iter.next();+ const oldValue = initial ? undefined : getValue(ctx._el);+ const iteration = ctx._iter.next(oldValue);ctx._isIterating = false;if (iteration.done) {ctx._isDone = true;}return updateCtxChildren(ctx, iteration.value);}@@ -345,14 +353,21 @@ function updateCtxChildren(ctx, children) {function commitCtx(ctx, values) {if (!ctx._isUpdating) {ctx._renderer.arrange(ctx._host,ctx._host.tag === Portal ? ctx._host.props.root : ctx._host._node,getChildValues(ctx._host),);}+ const value = unwrap(values);+ const schedules = Array.from(ctx._schedules);+ ctx._schedules.clear();+ for (const schedule of schedules) {+ schedule(value);+ }+ctx._isUpdating = false;- return unwrap(values);+ return value;}function unmountCtx(ctx) {

Notes:

- The

schedulemethod also passes the component’s rendered DOM nodes as the first argument of its callback. This is mainly helpful when using theschedulemethod in helper functions outside of component bodies. The benefit of using yield results as opposed to thescheduleargument is that using yield results allows us to visualize the rendering and accessing of rendered values in a linear fashion directly within the component.

Intermission #

At this point, we’ve implemented most of the logic for synchronous components in Crank. This is actually enough to write full-fledged applications.

Nevertheless, we will inevitably start to wonder: if we can use sync generator functions to write components, why can’t we use async functions and async generator functions to define components as well? The next steps will implement async components using these function syntaxes.

If you were already familiar with iterators, iterables and generators, you probably would not have had too much difficulty understanding the code and techniques we’ve seen so far. However, because we are now diving into concurrent code which makes heavy use of promises, things are about to get a little more difficult. This is a natural place to take a break, or to review the code we’ve written so far before continuing.

Step 11: Async Function Components #

Just as Crank leverages generator functions for stateful components, it also provides first-class support for promises, by allowing components to be defined as async functions as well.

To review, an async function is a special function syntax which prepends async before the function keyword (async function). This allows you to use the await operator within the function to read promises in a way which looks synchronous. Here is an example of an async function component in Crank.

async function DelayedGreeting({name}) {await new Promise((resolve) => setTimeout(resolve, 2000));return <div>Hello <span style="color: red">{name}</span></div>;}

Implementation #

--- a/crank.js+++ b/crank.js@@ -18,6 +18,10 @@ function isIteratorLike(value) {return value != null && typeof value.next === "function";}+function isPromiseLike(value) {+ return value != null && typeof value.then === "function";+}+class Element {constructor(tag, props) {this.tag = tag;@@ -125,62 +129,66 @@ function getChildValues(el) {export class Renderer {constructor() {this._cache = new WeakMap();}render(children, root) {let portal = this._cache.get(root);if (portal) {portal.props = {root, children};} else {portal = createElement(Portal, {root, children});this._cache.set(root, portal);}- update(this, portal, portal);+ const result = update(this, portal, portal);+ if (isPromiseLike(result)) {+ return Promise.resolve(result).then(() => getChildValues(portal));+ }+return getChildValues(portal);}create(el) {return document.createElement(el.tag);}patch(el, node) {for (let [name, value] of Object.entries(el.props)) {if (name === "children") {continue;} else if (name === "class") {name = "className";}if (name in node) {node[name] = value;} else {node.setAttribute(name, value);}}}arrange(el, node, children) {let child = node.firstChild;for (const newChild of children) {if (child === newChild) {child = child.nextSibling;} else if (typeof newChild === "string") {if (child !== null && child.nodeType === Node.TEXT_NODE) {child.nodeValue = newChild;child = child.nextSibling;} else {node.insertBefore(document.createTextNode(newChild), child);}} else {node.insertBefore(newChild, child);}}while (child !== null) {const nextSibling = child.nextSibling;node.removeChild(child);child = child.nextSibling;}}}@@ -228,29 +236,41 @@ function update(renderer, host, el) {function updateChildren(renderer, host, el, newChildren) {const oldChildren = wrap(el._children);newChildren = arrayify(newChildren);const children = [];- const values = [];+ let values = [];const length = Math.max(oldChildren.length, newChildren.length);for (let i = 0; i < length; i++) {const oldChild = oldChildren[i];let newChild = narrow(newChildren[i]);const [child, value] = diff(renderer, host, oldChild, newChild);if (oldChild instanceof Element && child !== oldChild) {unmount(renderer, oldChild);}children.push(child);if (value) {values.push(value);}}el._children = unwrap(children);+ if (values.some((value) => isPromiseLike(value))) {+ values = Promise.all(values).finally(() => {+ for (const oldChild of oldChildren.slice(length)) {+ if (oldChild instanceof Element) {+ unmount(renderer, oldChild);+ }+ }+ });++ return values.then((values) => commit(renderer, el, normalize(values)));+ }+for (const oldChild of oldChildren.slice(length)) {if (oldChild instanceof Element) {unmount(renderer, oldChild);}}return commit(renderer, el, normalize(values));}@@ -321,22 +341,25 @@ class Context {function stepCtx(ctx) {let initial = !ctx._iter;if (ctx._isDone) {return getValue(ctx._el);} else if (initial) {const value = ctx._el.tag.call(ctx, ctx._el.props);if (isIteratorLike(value)) {ctx._iter = value;+ } else if (isPromiseLike(value)) {+ return Promise.resolve(value)+ .then((value) => updateCtxChildren(ctx, value));} else {return updateCtxChildren(ctx, value);}}const oldValue = initial ? undefined : getValue(ctx._el);const iteration = ctx._iter.next(oldValue);ctx._isIterating = false;if (iteration.done) {ctx._isDone = true;}return updateCtxChildren(ctx, iteration.value);}

Just as in the implementation of generator components, we detect async components in stepCtx() solely by the return value of the component call. While there may be ways to identify async functions without calling them, this would again be an anti-pattern, insofar as it would prevent functions which returned promises but did not use async syntax from being used as async components.

Async components are “contagious” in that they make ancestor components update and commit asynchronously as well. Additionally, any refresh() or render() calls which attempt to render async components will now return promises, and all DOM mutations are deferred until the async components have settled. This logic is implemented in the updateChildren() function, where we return a promise of the commit() call if any child values are detected to be promise-like.

Step 12: Enqueuing #

Our async components work, but are problematic in that there can be multiple pending executions of the async component element at the same time. While this might not matter for the previously defined DelayedGreeting component, which uses a setTimeout()-based promise, this would be a problem for async components which make network requests or perform other I/O, insofar as your clients might inadvertently make too many concurrent requests over a short period of time. Do this too often and you may receive a sternly-worded email from a backend engineer!

async function UserGreeting() {const res = await fetch("/api/whoami");const name = await res.text();return <div>Hello <span style="color: red">{name}</span></div>;}renderer.render(<NetworkedGreeting />, app);renderer.render(<NetworkedGreeting />, app);renderer.render(<NetworkedGreeting />, app);renderer.render(<NetworkedGreeting />, app);renderer.render(<NetworkedGreeting />, app);// Expected: Fires 1 or 2 network requests.// Actual: Fires 5 network requests.

What we want is a way to limit the concurrency of async component elements, so that there is at most, one pending call for the component element, at any point in time.

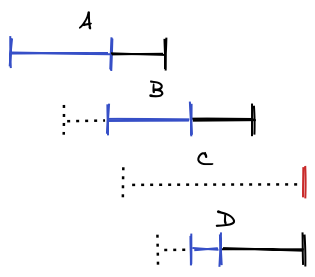

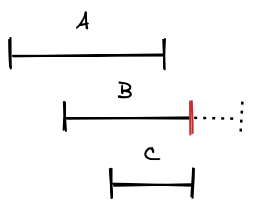

Before we continue, I’d like to introduce a visual notation for promises which we’ll use for the rest of this essay. This is a promise.

These diagrams will get more complicated, I promise. But for now, know that the horizontal axis represents time, the left edge represents when the promise was created and the right edge represents when the promise settles.

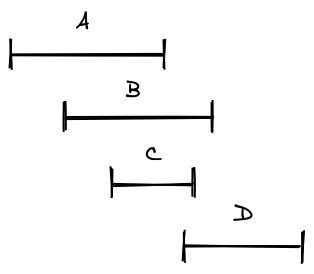

Given this notation, we can represent multiple calls to an async function as follows.

What we want for async components is a strategy which coalesces these promises so that there is only one pending run of a component element at any point in time. Visually, this would mean that none of these line segments overlap.

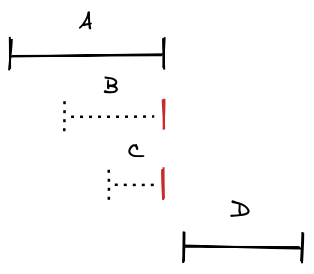

One possible technique we could use is hitching, where we resolve concurrent calls to the currently pending run, if one exists. We call this technique “hitching” because it’s as though concurrent calls are hitching a ride on the pending call rather than creating a new promise.

This strategy would transform the previous diagram to the following one.

The promises B and C resolve to the promise A, because they are created while A is still pending. We use a dotted line to indicate that these promises don’t actually perform any work, and we use the red trailing edge to indicate that these promises have resolved to some other call. Because D starts after A finishes, it is its own independent promise.

We can demonstrate the algorithm for this strategy by implementing it as a higher-order function which takes an async function and returns a modified function which exhibits this hitching behavior.

function hitch(fn) {let inflight;return function hitchWrapper(...args) {if (!inflight) {inflight = Promise.resolve(fn(...args)).finally(() => {inflight = undefined;});}return inflight;};}

The hitch() function defines an inflight variable in the closure of the returned wrapper function. When called, the wrapper function checks the inflight variable, and if it is not set, assigns to it a promise which resolves to a call to the original function. The wrapper function returns this inflight promise, regardless of whether or not it was set by the call. Finally, we use Promise.prototype.finally() to clean up the inflight promise when it settles, so that new calls to the original function can be made.

While this approach reduces the number of concurrent runs of an async function to one, it wouldn’t be correct for our use-case, insofar as by the time all promises settled, we might not yet have had an async run with the latest props for each component. Instead, we need a strategy which enqueues runs of async component functions so that when all promises settle, the element tree and rendered values reflect the latest props and state. We can tweak the hitch() function above as the alternative higher-order function enqueue() to demonstrate the logic we want.

function enqueue(fn) {let inflight;let enqueued;let latestArgs;return function enqueueWrapper(...args) {latestArgs = args;if (!inflight) {inflight = Promise.resolve(fn(...latestArgs)).finally(() => {inflight = enqueued;enqueued = undefined;});return inflight;} else if (!enqueued) {enqueued = inflight.then(() => fn(...latestArgs)).finally(() => {inflight = enqueued;enqueued = undefined;});}return enqueued;};}

We’ve added two more variables to the wrapper function’s scope, enqueued and latestArgs . The returned wrapper function first checks if there is an inflight promise, and creates and returns this inflight promise if none exists. If an inflight promise does exist, the wrapper function checks if there is an enqueued promise of the original function, and creates it if it doesn’t exists. This enqueued run first waits for the inflight run to fulfill before calling the function again, and calls the function with latestArgs, which we set to the latest call’s arguments whenever the wrapper fuction is called. We return the enqueued promise whether or not the current wrapper call had created it. Finally, we use Promise.prototype.finally() on both the inflight and enqueued promises to advance and clear the queue.

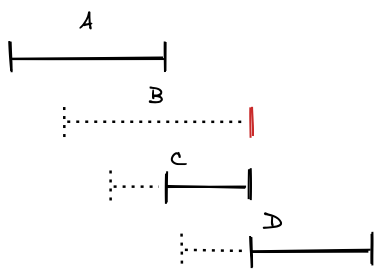

This strategy can be expressed as the following promise diagram.

In this diagram, because B and C are created while A is pending, we enqueue another run. However, only C actually does work, because by the time A finishes, we only re-invoke the function with C’s arguments, while B’s arguments would have been overwritten. This is a useful behavior for async components, because we don’t really care about obsolete props or element trees. Lastly, D starts while C is pending, so we schedule another run for D. Note that the original function is not invoked until the current run settles, so we again have a situation where there is only one concurrent run of the original function at a time.

Implementation #

Here is the implementation of this enqueuing strategy for components.

--- a/crank.js+++ b/crank.js@@ -307,33 +307,35 @@ function unmount(renderer, el) {class Context {constructor(renderer, host, el) {this._renderer = renderer;this._host = host;this._el = el;this._iter = undefined;this._schedules = new Set();+ this._inflight = undefined;+ this._enqueued = undefined;// flagsthis._isUpdating = false;this._isIterating = false;this._isDone = false;}refresh() {- return stepCtx(this);+ return runCtx(this);}schedule(callback) {this._schedules.add(callback);}*[Symbol.iterator]() {while (!this._isDone) {if (this._isIterating) {throw new Error("Context iterated twice without a yield");}this._isIterating = true;yield this._el.props;}}}@@ -364,9 +366,32 @@ function stepCtx(ctx) {return updateCtxChildren(ctx, iteration.value);}+function advanceCtx(ctx) {+ ctx._inflight = ctx._enqueued;+ ctx._enqueued = undefined;+}++function runCtx(ctx) {+ if (!ctx._inflight) {+ let value = stepCtx(ctx);+ if (isPromiseLike(value)) {+ value = value.finally(() => advanceCtx(ctx));+ ctx._inflight = value;+ }++ return value;+ } else if (!ctx._enqueued) {+ ctx._enqueued = ctx._inflight+ .then(() => stepCtx(ctx))+ .finally(() => advanceCtx(ctx));+ }++ return ctx._enqueued;+}+function updateCtx(ctx) {ctx._isUpdating = true;- return stepCtx(ctx);+ return runCtx(ctx);}function updateCtxChildren(ctx, children) {

We define another context function runCtx(), which is where the enqueuing behavior is implemented, and call this function instead of stepCtx() in the refresh() method and the updateCtx() function. Rather than implementing the enqueuing algorithm with a higher-order function, we store the inflight and enqueued promises directly on component context. We do this because we’ll need to modify the algorithm in various ways for later steps.

Because the enqueuing state is stored on contexts, enqueuing only happens for components which are rerendered. If a different element is rendered into an old component element’s position, the old context is blown away, so no async enqueuing would occur. This means that element enqueuing happens based on the same element diffing algorithm which governs DOM node re-use and stateful components.

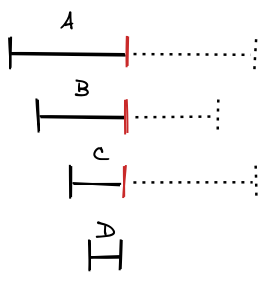

Step 13: Async Children #

Another way to think about the enqueuing behavior in the previous step is that components are “blocked” from updates while they’re pending. However, the enqueuing algorithm we’ve implemented so far might “over-block,” in the sense that components currently block not only for their own async executions, but also for their children’s async executions as well. This enqueuing behavior will, for instance, cause a synchronous function component with async children to block for the duration of its children’s async rendering time, even though there really isn’t a need for sync function components to block at all.

Therefore, we need a way to distinguish a component’s own execution time from the rendering time of its children, and block the component accordingly. For maximal concurrency, a sync function component should never block for any reason, while an async function component should only block while the async function itself is executing, but not for the rendering of its children.